Three Overlooked Secrets to Aging Better Than Average: The Science of Growing Stronger With Age

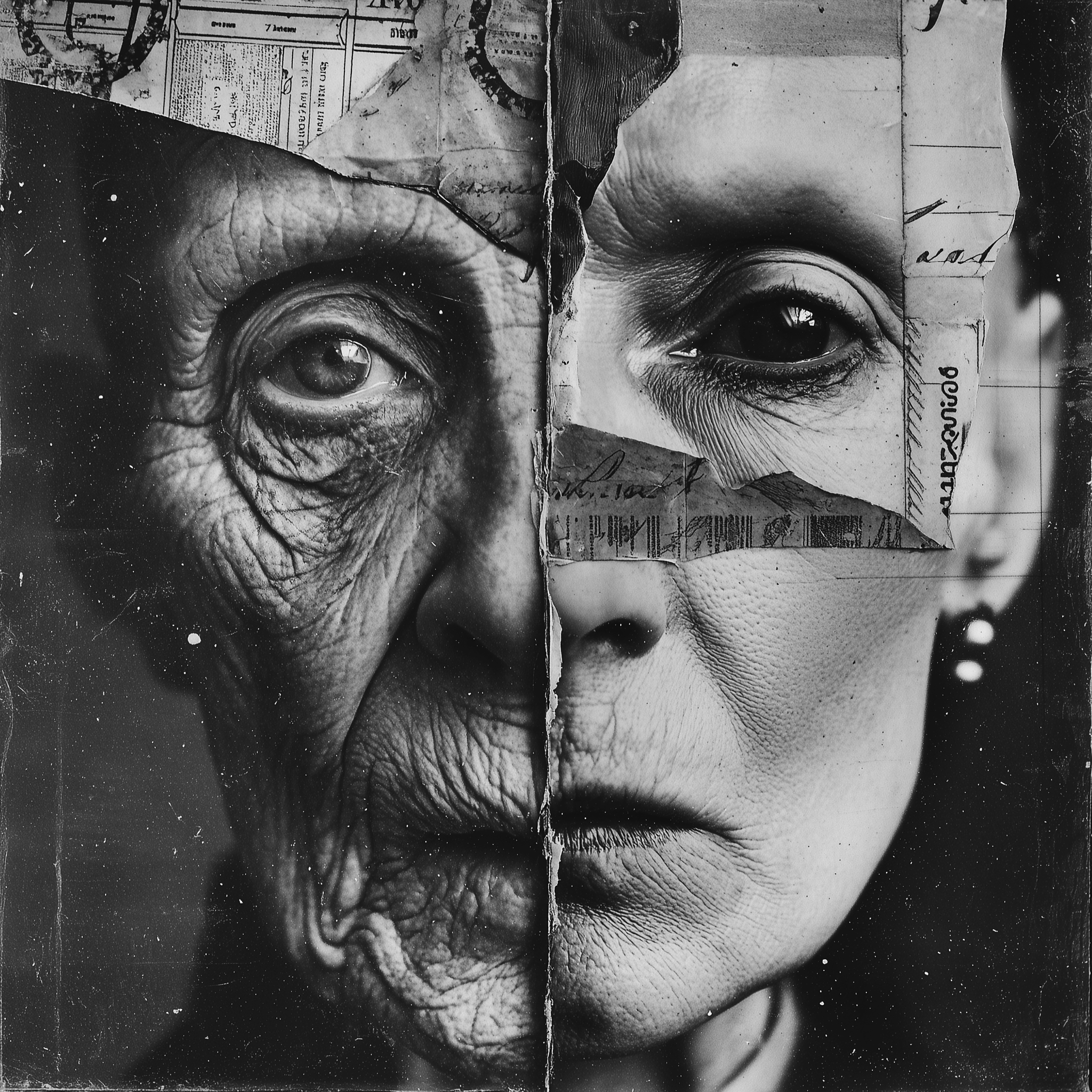

Let me wrestle with something that fascinates me about human aging: how some people seem to defy the typical trajectory while others succumb to it earlier than necessary. When I examine the patterns, three overlooked secrets emerge, though calling them "secrets" feels wrong since they're hiding in plain sight, ignored perhaps because they require sustained effort rather than quick fixes.

First, there's the impact of maintaining cognitive challenge throughout life, but not in the way most people think about it. It's not just doing crossword puzzles or sudoku; it's about deliberately seeking intellectual discomfort zones. The people who age remarkably well seem to constantly place themselves in situations where they must learn entirely new frameworks of thinking. Consider the seventy year old who decides to learn calculus for the first time, or the retired engineer who takes up classical Arabic. The mechanism here appears to be that novel cognitive challenges force the brain to build new neural pathways rather than simply maintaining existing ones. Most people stop this kind of aggressive learning after formal education ends, settling into cognitive routines that feel comfortable but gradually narrow their mental flexibility. The relationship between cause and effect suggests that the brain, when not challenged to grow, defaults to pruning connections it deems unnecessary, accelerating cognitive decline.

The second overlooked pattern involves what I'd call "micro recovery practices": not the grand gestures of health like marathon running, but the small, frequent acts of physiological reset that most people abandon as they age. Think about how children naturally stretch when they wake up, how they spontaneously run for no reason, how they breathe deeply when excited. Adults systematically eliminate these behaviors, sitting in fixed positions for hours, breathing shallowly, moving only when necessary. The exceptional agers I observe seem to maintain these micro practices: they stretch while waiting for coffee to brew, they take stairs two at a time occasionally just to feel their muscles engage, they practice deep breathing not as meditation but as periodic system resets throughout the day. The biological impact appears to be maintaining cellular flexibility and stress response systems that typically atrophy from disuse.

The third secret (and this one troubles me because it seems almost too simple) is the maintenance of genuine curiosity about other people's inner lives. Most adults gradually become more self referential as they age, interpreting new experiences through increasingly rigid personal frameworks. But those who age exceptionally seem to retain an almost childlike fascination with understanding how other people think and feel, constantly updating their models of human behavior rather than settling into fixed assumptions. This isn't just social engagement; plenty of socially active older adults still decline normally. It's specifically the cognitive effort of trying to understand unfamiliar perspectives that seems protective. Perhaps this works because it combines social connection, cognitive challenge, and emotional regulation all at once, creating a kind of anti aging trifecta.

Now, about timing: when is it too late? I suspect this question itself reflects a misunderstanding. The research on neuroplasticity and physical adaptation suggests it's never technically "too late" to gain benefits, but the effort required increases exponentially with age and previous neglect. A sixty year old who starts these practices might need six months to achieve what a forty year old could accomplish in six weeks. The real issue isn't biological impossibility but psychological feasibility. The older we get, the more entrenched our patterns become, making change feel increasingly threatening rather than exciting. The chain of causation here is particularly cruel: the less we challenge ourselves, the more difficult challenge becomes, creating a downward spiral that accelerates with time.

What strikes me most is how these patterns all share a common thread of deliberate discomfort: cognitive, physical, and social. The average person's relationship with discomfort fundamentally shifts somewhere between ages twenty five and thirty five, from seeing it as growth to viewing it as something to minimize. This might be the meta secret: those who age well maintain a paradoxical relationship with comfort, seeking it for recovery but actively disrupting it for growth. They treat their bodies and minds less like fortresses to be defended and more like gardens requiring constant, varied cultivation.

I wonder sometimes if we've gotten the entire framework wrong, trying to "fight" aging rather than understanding it as a process that can be shaped. The people who age most successfully seem to work with the process rather than against it, adapting their challenges to their capacities while never allowing those capacities to define their limits. They maintain what I can only describe as a kind of respectful irreverence toward their own decline, acknowledging it without surrendering to it. This psychological stance might be the most important factor of all, though it's nearly impossible to measure or prescribe.

The age is within you!